Universidad Europea de Valencia

Nuria.alabau@universidadeuropea.es

Universidad Europea de Valencia

Lorena.perez2@universidadeuropea.es

Universidad Europea de Valencia

Fatima.gomez@universidadeuropea.es

Abstract. This article posits the need for contemporary organizations to move from a traditional Organizational Culture model to an Innovative Organizational Culture model that incorporates values, philosophies and work practices that can engage and motivate the latest generations of employees. Two technological startups located in the entrepreneurial hub of La Marina in Valencia (Spain) are analyzed. Starting from an initial qualitative approach, an “ad hoc” questionnaire focusing on Organizational Culture is designed to ascertain how employees perceive their culture, detect which values and innovative management practices they most appreciate, and determine whether different generations of employees perceive the Organizational Culture of their company differently. From the results obtained, an Innovative Organizational Culture model is proposed that takes into account new cultural factors such as enjoyment, flexibility, teamwork, proactivity, effective communication, work challenges and innovation from an intergenerational perspective.

Keywords: Organizational culture; innovation; startup; commitment; generational diversity.

Explorando la cultura organizacional innovadora en startups de ecosistemas tecnológicos

Resumen. Este artículo plantea la necesidad de que las organizaciones contemporáneas muden desde una Cultura Organizacional tradicional a un modelo de Cultura Organizacional Innovadora que incorpore valores, filosofías y prácticas de trabajo capaces de comprometer y motivar a las nuevas generaciones de empleados. En concreto, se analiza la Cultura Organizacional de dos startups tecnológicas ubicadas en el Hub de La Marina de Valencia (España). A partir de una primera aproximación cualitativa, se diseña un cuestionario sobre Cultura Organizacional “Ad hoc”, con el objetivo de descubrir cómo perciben los empleados su cultura, detectar cuáles son los valores más apreciados, y las prácticas de gestión innovadoras y constatar si existían diferentes percepciones hacia la CO según la generación de los empleados. A partir de los resultados obtenidos, se propone un modelo de Cultura Organizacional Innovadora que contemple nuevos factores culturales como el disfrute, la flexibilidad, el trabajo en equipo, la proactividad, la comunicación efectiva, los retos laborales y la innovación, teniendo en cuenta la perspectiva intergeneracional.

Palabras clave: Cultura organizacional; innovación; startup; compromiso; diversidad generacional.

The complexity of VUCAH (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity and Hyperconnectedness) environments creates an accelerated scenario full of unexpected changes and constant transformations. This environment forces companies to be flexible, ambidextrous and innovative and to implement new values and new work practices (Denison et al., 2012; Huicab-García, 2023). In this context, Organizational Culture (OC) plays a fundamental role as a tool for transmitting values and generating a commitment to human resources. However, OC needs to evolve and adapt to new environments and the national and local contexts in which it develops. It also needs to align itself with the values and philosophy of the new generations of entrepreneurial leaders and workers who make up the innovative companies of the 21st century.

Taking labor generational diversity into account is key to managing people in contemporary organizations. Almost three decades ago pioneering authors in studies of generational talent warned of the importance of managing generational diversity and the need to address the different expectations and work styles of the different generations. Other studies carried out in Spain by Generacciona (2023) show how generations such as Generation Y (1982-1992) and Generation Z (1993-2003) coexist in companies and point out their different attitudes and challenges in the work environment. When OC is implemented, the workforce’s generational diversity must be taken into account. Incorporating Generation Y (“digital natives 1.0”) and Generation Z (“digital natives 2.0”) (Linne, 2014) into companies, and especially into technology startups, requires the companies’ OC to adapt to these generations in aspects such as values and expectations, communication styles, adoption of technology, and leadership styles (Gómez Sota & Moldes, 2021).

It is interesting, therefore, to determine which aspects define and condition innovative OC (hereafter IOC) on account of their influence on organizational elements and company results (Luu & Venkatesh, 2010; Pedraza-Rejas et al., 2021) as well as their ability to adapt to VUCAH and retain new generational talent.

This study is especially relevant in entrepreneurial ecosystems led by startups and scaleups (with persistent rapid growth to deliver a viable business model; Tippmann et al., 2023), where IOC is an identity hallmark and a fundamental pillar for boosting engagement and attracting talent (Oh et al., 2016; Gerónimo et al. 2020), particularly in technology companies located in these entrepreneurial clusters owing to their recent proliferation and their potential to transform society.

In this article we analyze the IOC of two technological startups, namely Zeus and Sesame, in the entrepreneurial ecosystem of La Marina (an innovative business hub in the Valencian Community, Spain) in 2016 and 2015, respectively. La Marina is a public space with an area of over one million square meters in which innovation, leisure and nautical activities coexist. Zeus is dedicated to analyzing large amounts of data (dashboards) while Sesame is involved in creating HR applications. Although both organizations are legally independent, they are considered a single company because they have the same CEO, strategy, location and OC. Our main objective is to analyze the characteristics of their IOC to detect which variables of their culture are innovative (as perceived by their employees) and which are the most valued according to the generation to which their workers belong.

Since the inception of Industry 5.0 a revolution in OC has taken place over several companies through collaboration, agility, employee empowerment and adaptation to rapid technological advancements. This transformative shift reflects a dynamic landscape in which human-machine collaboration defines the essence of an organizational culture that leads to innovative hubs (Grande & Peña, 2023).

This introduces the concept of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. This refers to the context and environment (actors and factors) that enhances, favors and drives the creation and growth of new business projects and ideas (Kantis & Federico, 2020) and identifies the entrepreneur as a central actor (Lastra et al., 2022; Cuc, 2022). In this space, innovative public and private companies, startups and scaleups coexist to create their own ecosystem with specific characteristics that favor the development of IOC and sustainable companies.

According to Isenberg’s study (2010), an entrepreneurial ecosystem is characterized by the support of a country’s government (aid, tax incentives, etc.), financing (ability to attract external finance and raise funds from banks and crowdfunding), culture (social and organizational factors specific to each region), support (the existence and support of mentors, accelerators and business networks), human capital (the ability to attract and retain talent), and markets (reference consumers, distribution channels, etc.).

A multitude of entrepreneurial ecosystems and hubs in which the highest levels of innovation and business creativity are concentrated coexist nationally and internationally. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Index of The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute (GEDI, 2020), the ranking of the most well-known and influential entrepreneurial ecosystems is led by the USA (Silicon Valley, etc.), the UK and the Netherlands. In recent years, however, other strategic locations have improved their positions and reputation, including Spain, which climbed from 34th in the world ranking in 2018 to 25th in 2020.

According to GEM Spain (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2021) and its 2020-2021 report, the Spanish entrepreneurial ecosystems that are ranked above the Spanish average and close to the best-valued entrepreneurial ecosystems in Europe are those of Catalonia, the Basque Country, the Valencian Community, and Navarre.

Since Schein’s first studies, conducted in the 1970s, the concept of OC has led to many studies of management, especially in relation to concepts such as organizational intelligence (Palacios-Maldonado, 2000). Early authors such as Pascale and Athos (1981) and Ouchi and Wilkins (1985) focused on the relationship between culture and business effectiveness. Between the 1980s and the 2000s, studies emphasized the relationship between culture and innovation (Pereira et al., 2020).

In this context, OC encompasses the values, norms and beliefs shared by the members of an organization. Understanding and studying OC facilitates cohesion, collaboration and goal alignment among the members of a company. OC analysis also focuses on aspects such as common goal orientation, which influences how objectives are set and pursued within an organization. Strong, well-defined OC promotes a sense of shared purpose and direction, improves communication and collaboration among workers, and makes it easier for employees to work together toward common goals. Once OC is understood and embraced by the workforce, patterns can be identified that promote efficiency and effectiveness (Schein, 1993; Cameron & Quinn, 2006; Chunhui et al., 2024).

OC is also fundamental to attracting, retaining, and reducing the turnover of talent. In this context, OC enables companies to deal with situations of change by preventing it from hindering the implementation of key processes, technologies or strategies.

Two influential models or theories have traditionally been analyzed in the field of OC: the Clan Theory (Schein, 1993; Cameron & Quinn, 2006), which considers organizations as clans or communities in which members share values, beliefs, norms and/or traditions; and Denison’s DOCS Model (Denison & Mishra, 1995), which analyzes four dimensions (involvement, consistency, adaptability, and mission).

Recent years have seen a proliferation of studies examining IOC in ecosystems and startups (Hervás & Hernández, 2020). These studies have analyzed the relationship between innovation, culture, creativity, continuous learning, collaboration and autonomy. According to Paul and Rosado-Serrano (2019), for example, to foster innovation in SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises) and startups, companies must have a culture that is open to change, collaborative and based on experimentation and tolerance, which are factors of IOC. In the same vein, Di Vaio et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review of the relationship between entrepreneurial culture and innovation in startups and identified the key elements of entrepreneurial culture.

Innovation has traditionally been associated with technological, industrial or product aspects. Nowadays companies and organizations, especially newly created ones of a technological nature, must also adopt innovation as a strategic part of their OC, thus resulting in IOC. Naranjo-Valencia and Hernández (2018:15) refer to IOC as “the multidimensional atmosphere that includes the shared values, assumptions and beliefs of an organization’s members that make it prone to explore new opportunities and knowledge and generate innovation in order to respond to market demands”. A company with an IOC is one that considers market trends and social, economic and environmental demands and introduces this concept into its business model and the foundations of its organizational culture (Hernández, 2021). IOC implies opting for flexibility (in working and understanding the day-to-day running of the organization), designing flat organizational structures in which any worker can take decisions and propose ideas, promoting collaborative teamwork (Rueda-Barrios et al., 2018), and affording workers a high degree of autonomy because they are “trustworthy”. IOC is also based on individual and group incentives whereby goals are shared as well as on believing in and caring for human capital from its recruitment and retention to the training and promotion of talent (Cohen-Granados et al., 2020).

An IOC also involves having an open communication system in which ideas can emerge at any level of the organization (McLean, 2005), understanding error as part of the process of innovation and improvement, and having a clear customer orientation (the customer as lighthouse). In this culture, workspaces are open environments where knowledge and information flows are shared, thus enhancing collaboration between departments and people (Stanley et al., 2014; Aslan & Atesoglu, 2021). Transparency, innovation and proactivity are among the corporate values that underpin its foundations. Finally, companies with an IOC understand change as a natural component of an organization and incorporate enjoyment and challenges into their organizational strategy since these concepts are directly related to the work climate and increase a worker’s sense of belonging to the organization (Pedraza-Rejas et al., 2021; Boonstra & Loscos, 2021).

This new way of understanding culture is being adopted by many organizations – from technology companies, startups or scaleups to leading companies in their sector who understand that being at the forefront and being competitive is not only about having good products or services but also about having an IOC (Trillo-Holgado et al., 2022). For example, in 2021 Heineken, with the Smart Working program, launched a new model of work organization characterized by flexibility and co-creation (El País-ICON, 2021). Another example is illustrated by the philosophy of companies in entrepreneurial ecosystems, such as Google, which focus on the three Fs: Focus (simplify, rationalize, make the office more efficient and understand its contribution to the company), Freedom (freedom to choose time and space, flexibility, remote work and structure), and Fun (innovative projects, welcoming spaces and a positive work environment).

The implementation of IOCs in organizations is associated with competitive advantages. VUCAH environments require new forms of governance, and innovation is proposed as a way to achieve them. Companies whose model is based on IOCs attract talent, improve employee engagement, achieve better financial results, promote creativity, and improve adaptability, etc. All these are significant benefits that can boost a company’s long-term success (Naranjo-Valencia & Hernández., 2018; Ospina et al., 2021).

This concept of culture is a complete departure from the traditional approach to organizational culture. Traditional culture is based on a vertical hierarchy, a lack of autonomy, a high degree of control and individualism, does not reward talent, is rigid and not very transversal, divides workspaces by hierarchy, and does not mention enjoyment. Consequently, this form of organizational culture does not enable the company to develop roots (Guerrero & López, 2003).

Table 1 below summarizes the differences between IOC and traditional culture according to the variables that explain culture:

Table 1. Traditional Organizational Culture versus Innovative Organizational Culture

Cultural variables |

OC |

IOC |

Flexibility |

Rigid and inflexible structures |

Flexible structures |

Autonomy |

Low degree of autonomy Vertical hierarchy |

High degree of autonomy Horizontal hierarchy |

Teamwork |

Individual goals Individual workspaces |

Common goals and team challenges Agile office Talent attraction and retention |

Proactivity |

React to change |

Anticipate change |

Transparency |

Vertical communication Lack of transparency |

Open communication |

Enjoyment |

Effort culture; error penalty |

Enjoyment culture in the workplace |

Innovation |

Risk aversion |

Measured risk |

Source: Author’s own.

Based on the above we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Zeus and Sesame have implemented a cohesive and innovative organizational culture.

H2: The perception of the values of a company’s innovative organizational culture depends on the age or generation of that company’s employees.

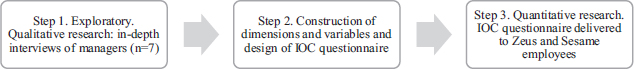

The results presented in this article derive from a study of IOC conducted in two companies (Zeus and Sesame) in 2021 and 2022 that combined qualitative (focused interviews) and quantitative (questionnaire) methodology. The first (exploratory) phase determined how managers described and transmitted OC to their teams and this information was then used to design the questionnaire.

The procedures for the study of OC comprised a range of methodological procedures. The qualitative approach provided a richer, more comprehensive view of culture and a more direct approach to the contexts and subjects (Pértegas & Fernández, 2002). This approach is useful for discovering the most symbolic component of OC, i.e. values and beliefs, which correspond to level 1 of culture as defined by Schein (1978).

This qualitative approach was then complemented by a quantitative methodology that collected and examined the data objectively based on dimensions defined at the beginning of the study.

Several quantitative research studies have focused on IOC in relation to startups (Aldianto et al., 2021; Van Looy, 2021). All agree that a quantitative approach helps to analyze in detail the relationship between variables such as OC business performance, adaptability, culture and leadership. Our quantitative study aimed to describe the type of IOC developed by the two companies and check whether it can be classified as an IOC. We also aimed to determine the extent to which this IOC has been implemented in these companies and examine its perception among their respective workforces. Taking the above into consideration, in this paper we focus on results from the quantitative phase, i.e. the questionnaire that was completed by all employees of each company. Below is a schematic representation of the phases involved in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Methodology

Source: Author’s own.

First, an exploratory study was conducted based on semi-structured focused interviews with the managers of the participating companies. These interviews took into account the diversity of profiles to, for example, gather information on the managers’ perceptions of IOC and their understanding of its current implementation. Seven interviews were conducted with managers from different areas of the companies in March and April 2021. To conduct the sampling, we used the saturation criterion while taking into account the most representative management areas and the gender of the interviewees. Table 2 shows the profiles of the interviewees.

Table 2. Sociodemographic profile of the interviewees

No. |

Gender |

Generation |

Position |

Company |

E1 |

Female |

Y |

Marketing Manager |

Sesame |

E2 |

Male |

Y |

CDO (Chief Data Officer) |

Zeus and Sesame |

E3 |

Female |

Y |

Marketing and Communication Manager |

Zeus |

E4 |

Female |

X |

People & Talent Manager |

Zeus and Sesame |

E5 |

Male |

X |

Zeus CDO |

Zeus |

E6 |

Female |

X |

Partnership Manager |

Sesame |

E7 |

Female |

Y |

CPO (Chief Product Officer) |

Sesame |

Source: Author’s own.

Some profiles are shared by both companies since they are part of the same group. The desire to implement the same culture in both companies and for that culture to be perceived as such by their employees is vitally important for the management of each company. The interviews were transcribed to facilitate transversal analysis of the interviewees’ responses. The categories of the transcripts were as follows: C1, definition of the company’s culture; C2, selection processes and onboarding; C3, types of work and spaces; C4, development and retention; C5, compensation and commitment; and C6, definition of the core of the OC is it innovative?

Our analysis of the interviews enabled us to gather information about the managers’ definition of OC in terms of values (e.g. humility, ambition, trust, transparency, proactivity and people) and work philosophy (e.g. teamwork, innovation, enjoyment, friendliness, flexibility, technology, adaptability and agility).

Conclusions on the values and work philosophy at Zeus and Sesame, as well as information obtained at interviews on which policies and work practices are considered innovative by the managers, were then used in the questionnaire. In addition to the theoretical models from which we started (Schein, 1993; Denison et al., 2012), this provided us with the foundation to design and structure an IOC questionnaire tailored to the context of our study of the participating companies.

An ad hoc questionnaire was prepared to ascertain the employees’ opinion of their OC, their degree of commitment and satisfaction with it, their degree of acceptance of it, and their perception of their OC as a possible IOC. The questionnaire comprised 26 questions, including closed questions on satisfaction, and Likert scales. These scales are commonly used to measure attitudes and, in studies of organizational climate and culture, to collect levels of agreement with various aspects to enable respondents to express their level of agreement or disagreement with each item (Bolaños-Medina & González-Ruiz, 2013). The Likert scales ranged from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (strongly agree). An open-ended question was included at the end of the questionnaire.

The content was designed by taking into account two dimensions of analysis: values and practices. Table 3 lists the categories included in the questionnaire by IOC value and variable analyzed.

Table 3. Questionnaire categories

Sociodemographic data of the interviewees |

I. OC - Values - Work philosophy - Organizational aspects - Labor policies |

II. Recruitment and onboarding |

III. Use of time and workspace |

IV. Development and retention |

V. Retribution and commitment |

VI. Closure |

Open question: OC improvements |

Source: Author’s own.

The questionnaire was reviewed and validated by the management of both organizations as well as by the heads of the key departments. A pre-test was then performed to conduct the final field study (Table 4).

Table 4. Quantitative study data

Universe |

N=196. Sesame and Zeus employees |

Dates |

April 2nd–May 23rd (2022) |

Sample |

n=146 |

Technique |

Online mixed self-reported questionnaire (QR) |

Data processing |

SPSS v.29 |

Source: Author’s own.

The questionnaire was of the self-reported type and was conducted online. Google Forms was used to create the questionnaire, which was distributed to the entire workforce of both companies in the form of a QR code. Two of the companies’ marketing managers informed the workers about the survey. During the time the questionnaire was open, the managers monitored participation and updated the researchers about it. The researchers checked the response rate daily until a valid value for the nature of the study was reached. The fieldwork was conducted between Monday May 23rd and Friday April 2nd (2022).

As our study population was finite and localized, the questionnaire was sent to the entire workforce of each company (i.e., to all departments and positions). At the time of the study, the companies had 196 employees in total and a final sample of n=146 responses was collected, this indicates that 75% of the total population was reached, with a confidence level of 96.7% and a margin of error of 3.3%.

The sociodemographic data of the sample collected were as follows. With regard to gender, 49.6% identified as female, 48.2% identified as male, and 2.1% identified as non-binary. Most of the sample (81%) belonged to the younger generations, i.e. Generation Z (39%; 18-29 years old) and Generation Y (42%; 30-40 years old), while 17% were classified as Generation X (41-51 years old). With regard to educational level, 72% had completed higher education and 26% had completed vocational training. The companies’ workforces are therefore young and well educated/well trained which, as we shall see, fully identifies with the values and philosophy they promote.

The results of the questionnaire were coded and analyzed using SPSS v.29 and a descriptive analysis (frequencies and averages) was conducted. To complement these results and test Hypothesis 2, ANOVA analysis by generations was conducted on IOC-related variables.

According to Rueda-Barrios et al. (2018), values are considered the core of an OC. Values are the representative seal that distinguishes a company, a basic element of its desired culture, and the set of fundamental principles that guide employees.

The employees were asked to consider the values, customs and habits, etc., that make up their company’s IOC. We assessed which of these were most valued regardless of whether they referred to Zeus or Sesame since both companies work as a single entity.

Teamwork and enjoyment (94.6% and 91.8%, respectively) were highlighted by employees as the most representative IOC values, followed by proactivity (91.2%), flexibility, autonomy, and innovation (each 86.4%). These values were highlighted by the managers in their interviews.

Proactivity also emerged as a positive and characteristic value of both companies. Defined as the action of anticipating possible changes, proactivity directly influences business results. Autonomy, which favors productivity and is associated with high levels of competitiveness (Schein, 1978), is perceived by employees as a value that is embedded into their company’s IOC.

Another value perceived with a high level of agreement (80.9%) is transparency. A transparent company is one that truthfully and concisely reports those aspects it considers important to convey so that stakeholders know what the company does and on what basis it makes decisions (Batlles de la Fuente & Abad-Segura, 2023; Santiago-Torner, 2023).

All employees unanimously consider that their company guarantees them flexibility (µ=4.58 out of 5). One of the policies valued most highly by employees in this area is the freedom to dress as they like (97.7%; µ=4.82 out of 5). Dress code is closely related to IOC since it favors inclusive and diverse cultures. According to a study by Deloitte (2019), the freedom to dress as one likes shows that a company has an IOC, whereas a conservative dress policy restricts employees’ freedom of expression and affects their performance (Table 5).

Table 5. IOC component: flexibility

|

Variables |

Frequency (%) |

Average |

Flexibility µ=4.58 |

Flexible hours |

95.7 |

4.58 |

Freedom to choose the workplace |

86.6 |

4.47 |

|

Dress code freedom |

97.7 |

4.82 |

|

Adaptation to change |

90 |

4.45 |

Source: Author’s own.

The above shows that an IOC requires a strong teamwork structure. The concept of individualistic work corresponds to a traditional OC that is far removed from the contemporary IOC of technology companies. Our results show that employees perceive teamwork as a fundamental pillar in their company’s OC (µ=4.47 out of 5). This highlights the importance employees attach to their workspaces being collaborative and open (95.7%; µ=4.66 out of 5). Dittes et al. (2019), who conducted a study on workspaces of the future, argued that although the workspace has been and may still be relevant for outcomes, where the work is done is not as relevant as when it is done. Collaborative or open spaces promote business effectiveness and efficiency thanks to factors such as creativity, equality, communication and problem solving. When it comes to problem solving, employees believe their IOC is less oriented towards understanding individual and group errors than it should be, which suggests that their OC still needs to work on this labor policy to become innovative (Table 6).

Table 6. IOC component: teamwork

|

Variables |

Frequency (%) |

Average |

Teamwork µ=4.47 |

Teamwork |

97.2 |

4.65 |

Open and collaborative workplaces |

95.7 |

4.66 |

|

Promotion |

97.5 |

4.61 |

|

Assumption of one’s mistakes as group mistakes |

78 |

3.96 |

Source: Author’s own.

Innovative organizations are characterized by effective and open communication styles, since open and transparent communication is a pillar of participative leadership that favors organizational commitment (Goleman & Drucker, 2018). Our results show that, according to the motto of the companies (People & Data) (Gómez Sota & Moldes, 2021; Gómez Sota et al., 2023), communication is one of the components that distinguish a company’s IOC via a communication system that is close and adapted to the new technologies and generations that make up the workforce (µ=4.44 out of 5). A policy that promotes easy communication with superiors has the highest average level of agreement (96.5%; µ=4.63 out of 5). Similarly, a policy that instills confidence in reporting to superiors also achieves a high average level of agreement (95.7%; µ=4.59 out of 5). On the other hand, a personalized communication policy has the lowest average level of agreement. Managing new practices by means of personalizing feedback is one of the challenges faced by these companies and an aspect for them to work on (Table 7).

Table 7. IOC component: Communication

|

Variables |

Frequency (%) |

Average |

Communication µ=4.44 |

Ease of communication with managers |

96.5 |

4.63 |

Personalizing feedback |

76.6 |

4.08 |

|

Confidence when talking to managers |

95.7 |

4.59 |

Source: Author’s own.

Enjoyment as a component of IOC is directly related to what in contemporary management is termed employee experience, which seeks an affective or attitudinal commitment. This affective model, based on the “experience” employees have with their organization, is divided into three dimensions: sensory experience, aesthetic experience, and emotional or entertainment experience (Ambler & Barrow, 1996). The latter, which refers to enjoyment at work, is directly related to the perception of performance. The IOC of companies with employees from the younger generations (generations Y and Z) incorporate, or should incorporate, this dimension. Indeed, in our case study we found that almost the entire workforce (95.7%; µ=4.65 out of 5) believes that their company is committed to enjoyment (Table 8).

Table 8. IOC component: enjoyment

|

Variables |

Frequency (%) |

Average |

Enjoyment µ=4.61 |

Celebration of milestones |

81.6 |

4.56* |

Commitment to enjoyment |

95.7 |

4.65 |

* This item was calculated on a two-point scale and recalculated on a five-point scale for the joint average of the enjoyment component

Source: Author’s own.

We also observed a moderately high level of agreement with the fact that milestones are celebrated in the company (81.6%). This practice, which assimilated by departments and the organization as a whole and is directly related to joint experience of the company, makes all employees feel part of the group’s success.

By implementing different organizational practices and transmitting culture, companies seek commitment from their employees. All theoretical models that explain the dimensions of IOC speak of the need to engage or involve people in the organization (Denison et al., 2012). In the present study we considered four items that reflect this commitment. The first, and the one with the highest level of agreement, is a willingness to remain in the company (almost 100% of staff members expressed the desire to stay with the organization).

Another aim of IOC is to encourage people who work in an organization to identify with their organization and its mission and vision. Identification with the company achieved an agreement of 85%, which suggests that the values of Zeus and Sesame are understood and assumed by the whole organization (Table 9).

Table 9. IOC component: commitment

|

Variable |

Frequency (%) |

Average |

Commitment µ=4.28 |

IOC transfer |

96.5 |

4.62 |

Desire to remain |

86.6 |

4.34 |

|

Identification with the company |

85.8 |

4.26 |

Source: Author’s own.

Companies with an IOC value innovation as part of their DNA. These companies are proactive, anticipate change and share a Kaizen philosophy of continuous improvement (Frick & De Frick, 2013). This value is also characteristic of companies in entrepreneurial ecosystems, where knowledge transfer and a commitment to improvement and innovation is a key, differentiating element (Arenal et al., 2018). Both companies in this study put this value into practice by rewarding innovation (81.5%; µ= 4.20 out of 5) because they believe that positive feedback and rewards motivate the workforce to also drive this value (Fisher, 2005). Similarly, innovation is also practiced, though to a lesser extent (75.2%; µ=4.02 out of 5) (Table 10), through the pursuit of perfectionism.

Table 10. IOC component: innovation

|

Variable |

Frequency (%) |

Average |

Innovation µ=4.11 |

Reward for talent and innovation |

81.5 |

4.20 |

Perfectionism |

75.2 |

4.02 |

Source: Author’s own.

An ANOVA test was conducted in which the variable ‘generation’ was estimated as the moderating factor for several variables affecting the construction of the companies’ IOC (Table 10). The generations considered were generations X, Y and Z. Regardless of the generation to which the employees belong, the only cultural organization value with a different perspective was adaptability: generation X (µ=4.71 out of 5) perceives its IOC as having a greater level of adaptability than generations Y (µ=4.53 out of 5) or Z (µ=4.31 out of 5).

Although the companies considered incorporating new forms of flexibility at work due to COVID-19 and the innovative nature of organization in terms of culture, the reality is different. Some organizational aspects have been incorporated. Generation X (µ=4.29 out of 5; µ=4.58 out of 5, respectively) views remote work and hybrid work as being encouraged by their IOC more than Generation Y (µ=3.83 out of 5; µ=4.03 out of 5) or Generation Z (µ=3.60 out of 5; µ=3.89 out of 5) do. Table 11 shows the disparity of opinions of work modality, which measures whether employees consider they are freely able to choose the type of work they do (remote, on site or hybrid). As we can see, they do not perceive that they have this freedom, with Generation Z being the most skeptical about this issue. With regard to choice of workspace, the generations revealed no significant differences. However, most employees choose to work in individual spaces (63.1%) followed by working at shared tables (24.8%), at home (8.5%), in leisure areas such as the terrace or cafeteria (2.8%), or other available spaces (0.7%).

Table 11. Descriptive and ANOVA analysis by generation and estimated variable

Generation |

Variables |

General average (out of 5) |

Average per generation (out of 5) |

ANOVA |

|

F |

Sig. |

||||

Z |

Adaptability |

4.51 |

4.31 |

3.134 |

<.05 |

Y |

4.53 |

||||

X |

4.71 |

||||

Z |

Remote work |

3.90 |

3.60 |

3.395 |

<.05 |

Y |

3.83 |

||||

X |

4.29 |

||||

Z |

Hybrid work |

4.16 |

3.89 |

4.370 |

<.05 |

Y |

4.03 |

||||

X |

4.58 |

||||

Z |

Work modality |

3.12 |

2.87 |

7.911 |

<.05 |

Y |

2.95 |

||||

X |

3.54 |

||||

Source: Author’s own.

Finally, both sets of employees consider that their IOC reflects the values of their generation, that their company is considered a reference in the entrepreneurial ecosystem of their geographic area, that their company works in the manner of a startup, that they are satisfied with their company, and that their IOC is shared with their organization as a whole.

In the current and changing global labor context, OC is a strategic pillar. This paper highlights the importance of constantly adapting and revising the traditional concept of OC and evolving towards an IOC. Indeed, companies in entrepreneurial ecosystems, which are at the forefront of techniques, products and work philosophies, are focusing on new ways of doing, thinking, and attracting and retaining talent through IOC. To adopt an IOC, which incorporates the new values and habits of the younger generations, is to utilize a cohesive axis of teams, a source of organizational commitment, and an innovative corporate strategy.

In relation to hypothesis 1, our results show that Zeus and Sesame are companies with an IOC, although in some respects this is still under construction. The IOC of these companies is largely based on the following six values:

•Flexibility: the OC of both companies is based on the concept of freedom in the workplace, which manifests itself in practices related to dress code freedom, flexible work hours, and adaptation to change.

•Teamwork: both companies have open and collaborative workplaces in which self-mistakes are assumed to be group mistakes.

•Effective communication: the companies’ policies are based on transparency, closeness and trust with their employees (Goleman & Drucker, 2018; Moreno-Domínguez et al., 2022).

•Enjoyment: this core IOC value from the perspective of generation Z is common to companies in innovative ecosystems in a practice assimilated by all departments and implemented in spaces specially prepared for this purpose.

•Commitment: this is reflected in the attitude of the companies’ employees, who display a strong sense of belonging to their company (corporate identification), accept and understand its IOC, and express a desire to remain within it.

•Innovation: this component of the companies’ DNA is a philosophy imbued in their processes, services and decision-making. The employees in this study consider that innovation has an expanding and multiplying effect on other processes that are not necessarily cultural, as Oksanen and Ståhle (2013) and others have also suggested.

We can conclude, therefore, that Zeus and Sesame have an IOC based on the six values outlined above. Their employees perceive these values positively as forming the basis of their work and encompassing a people-management philosophy that focuses on transmitting this culture to their employees. The adoption of the company’s motto, “People & Data”, by employees indicates that a people-based culture is indeed being conveyed.

This study also reveals that generation (the difference in the age of employees) influences the perception of IOC since hypothesis 2 suggests that this perception varies depending on the generational perspective (X, Y and Z).

Overall, our results have revealed a cohesive commitment to both companies from their human capital. This highlights the importance Zeus and Sesame employees place on their emotional, relational and daily experiences and challenges (Fun), flexible working hours and dress code (Freedom), and new workspaces (Focus).

Also revealed is a hybrid IOC model that pivots between a type of culture characteristic of a technological startup/scaleup (Google-style) and values such as innovation, flexibility, transparency, tolerance to error, and a clan-type identity culture (Schein, 1993; Cameron & Quinn, 2006). The latter is linked to a more Mediterranean tradition whose values are reflected in enjoyment, interpersonal relationships and celebrations, and which brings competitive advantages to Zeus and Sesame. These IOC features are strengths and attractions that are characteristic to both companies. They enable these companies to attract talent from younger generations who seek new environments and new ways of working and are committed both to people and innovative projects.

Several cultural differences by generation can also be highlighted. For example, although the companies’ IOC is based on the above six values, Generation Z believes that they still have room for improvement when it comes to workspaces, adaptation and working arrangements. Generations Y and X, on the other hand, are more positive in this regard. Their results can be directly linked to their positions in the companies (mainly senior management) and the fact that their generation has a more traditional understanding of what an IOC entails thanks to their education. In view of these findings, hypothesis 2 can be partially accepted.

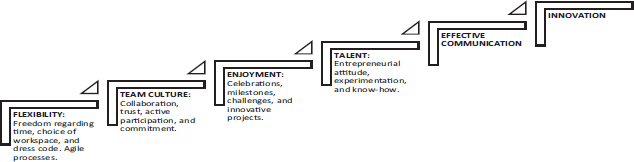

From our results we propose the following IOC model. This model is based on the values, habits and customs that are assumed and appreciated by the new generations and which lead to enjoyment, flexibility, team culture, talent, effective communication and innovation.

Figure 2. IOC ladder

Source: Author’s own.

This IOC ladder has practical implications for the management of companies in general and of technology companies in particular. Companies should employ a strategy to climb the rungs of this ladder and commit themselves to transformational, dedicated and intergenerational leadership styles. Agile and flexible processes and methods are also key to reaching the milestones on this ladder since they enable employees to develop skills, progress and feel part of a group. Companies should also design selection and onboarding processes focused on finding employees who share this philosophy and appreciate their IOC values. Performance evaluation and incentive processes must be objective, regular and personalized (generation and position) to enable the company to scale the IOC ladder. Communication is another key element since the managers of companies with an IOC must communicate this culture to their workforce transparently and comply with its values. Finally, the role of HR management should be reviewed and adapted to enable the company to effectively implement the IOC ladder.

Companies that wish to scale the ladder must begin by creating flexible and hybrid workspaces to develop a collaborative environment that focuses on the team rather than the individual (team culture). The next step is to focus on holding celebrations (social and festive aspects) and rewarding success (enjoyment). The IOC must then help to generate talent by attracting, training and retaining it. Finally, innovation must permeate every step of the IOC ladder. In conclusion, managers must meet the challenge of maintaining an IOC that retains the talent of several generations not only through an emotional salary and “attractive” practices (as in the cases we have studied) but also through innovative processes of performance evaluation, promotion and development in line with the profiles and demands of such a competitive sector as the technology sector. Otherwise, the IOC will cease to be an element for commitment and retention.

Finally, it would be interesting and enriching for future research to consider a third hypothesis that takes into account the technological effect on organizational change suggested in the study by Grande and Peña (2023).

Aldianto, L., Anggadwita, G., Permatasari, A., Mirzanti, I. R., & Williamson, I. O. (2021). Toward a Business Resilience Framework for Startups. Sustainability, 13(6), 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063132

Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185-206. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1996.42

Arenal, A., Armuña, C., Villaverde, S. R., & Feijóo, C. (2018). Ecosistemas emprendedores y startups, el nuevo protagonismo de las pequeñas organizaciones. Economía industrial, 407, 85-94. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6535710

Aslan, M., & Atesoglu, H. (2021). The effect of innovation and participation as workplace values on job satisfaction and the mediating effect of psychological ownership. SAGE Open, 11(4), 215824402110615. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211061530

Batlles de la Fuente, A., & Abad-Segura, E. (2023). Exploring research on the management of business ethics. Cuadernos de Gestión, 23(1), 11-21. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.221694ea

Bolaños-Medina, A., & González-Ruiz, V. (2013). Deconstructing the Translation of Psychological Tests. Meta: Translators’ Journal, 57(3), 715-739. https://doi.org/10.7202/1017088ar

Boonstra, J., & Loscos, F. G. (2021). Cambio organizativo: Juego, colaboración y diversión. Harvard Deusto Business Review, 309, 60-68. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7826276

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. R. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: based on the Competing Values framework. Personnel Psychology, 59(3), 755-757. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00052_5.x

Chunhui, L., Sorayaei, A., & Ahmad, A. (2024). The Impact of Transformational Leadership on the Work Performance of University Teachers through the Mediation of Organization Culture: Literature Review. UCJC Business And Society Review, 21(1), 260-299. https://journals.ucjc.edu/ubr/article/view/4610/3313

Cohen-Granados, J., Linares-Morales, J., & Briceño-Ariza, L. J. (2020). Caracterización de la cultura innovativa en la cooperación universidad-empresa. IPSA Scientia, Revista Científica Multidisciplinaria, 5(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.25214/27114406.963

Cuc, J. E. (2022). El ecosistema emprendedor como estructura para la cocreación de valor y redes de cooperación. Eco, 26(1), 1-38. https://doi.org/10.36631/eco.2022.26.01

Deloitte (2019). Unconvering talent: A new model of inclusion. https://shorturl.at/hCHP5

Denison, D. R., & Mishra, A. K. (1995). Toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness. Organization Science, 6(2), 204-223. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.2.204

Denison, D. R., Nieminen, L. R. G., & Kotrba, L. (2012). Diagnosing organizational cultures: A conceptual and empirical review of culture effectiveness surveys. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(1), 145-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2012.713173

Di Vaio, A., Palladino, R., Pezzi, A., & Kalisz, D. (2021). The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. Journal of Business Research, 123, 220-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.042

Dittes, S., Richter, S., Richter, A., & Smolnik, S. (2019). Toward the workplace of the future: How organizations can facilitate digital work. Business Horizons, 62(5), 649-661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2019.05.004

El País-ICON (2021). Revolución ‘smart working’: cuando los empleados deciden cómo quieren trabajar. https://shorturl.at/jRSX4

Fisher, J. G. (2005). How to run successful incentive schemes. Kogan Page Publishers.

Frick, A. M., & De Frick, S. T. F. (2013). Gestión y desarrollo de empresas innovadoras. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 8, 125-126. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-27242013000300063

GEDI (2020). The Digital Platform Economy Index 2020. https://shorturl.at/akBSV

Generacciona (2023). Estudio de Talento Intergeneracional - Generacciona - Queremos accionar y unir el talento de todas las generaciones. https://generacciona.org/estudio-talento-intergeneracional/

Gerónimo, R. K. M., Puente, C. S. L., & Castro, A. S. (2020). Gestión administrativa y gestión de talento humano por competencias en la Universidad Peruana Los Andes, Filial Chanchamayo. Revista Conrado, 16(72), 262-268. http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/rc/v16n72/1990-8644-rc-16-72-262.pdf

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) (2021). 2020-2021 Global Report. https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-20202021-global-report

Goleman, D., & Drucker, P. F. (2018). Liderando personas. Profit Editorial.

Gómez Sota, F. & Moldes, R. (2021). Hacia la construcción de un modelo de liderazgo intergeneracional. Revista Internacional de Organizaciones, 25-26, 127-150. https://doi.org/10.17345/rio25-26.127-150

Gómez Sota, F., Moldes, R., Alabau-Tejada, N., & Pérez-Alfonso, L. (2023). Caso práctico. Zeus y Sesame: un modelo de cultura corporativa innovadora. Harvard Deusto Business Review, 135. www.harvard-deusto.com. https://www.harvard-deusto.com/caso-practico-zeus-y-sesame-un-modelo-de-cultura-corporativa-innovadora

Grande, R., & Peña, A. V. (2023). Emerging Digital Technologies in the Workplace. 3D Printing, Work Organization and Job Quality at the Airbus Spain Case Study. International Journal Of Innovation And Technology Management, 20(06). https://doi.org/10.1142/s0219877023500359

Guerrero, R. F., & López, S. V. (2003). Una nueva cultura organizativa orientada a la innovación: un nuevo marco de relaciones laborales. Informació Psicològica, 81, 12-20. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4534492

Hernández, J. R. (2021). Cultura organizacional para la sostenibilidad empresarial. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo, 9(3). https://coodes.upr.edu.cu/index.php/coodes/article/download/450/823

Hervás, D. S., & Hernández, B. J. S. (2020). Organizaciones nativas responsables: la RSC en la cultura de los startups digitales españolas. Prisma Social: Revista de Investigación Social, 29, 138-154. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7470985.pdf

Huicab-García, Y. (2023). Gestión del talento humano en el entorno BANI. 593 Digital Publisher CEIT, 8(1-1), 155-165. https://doi.org/10.33386/593dp.2023.1-1.1533

Isenberg, D. (2010). The big idea: how to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/06/the-big-idea-how-to-start-an-entrepreneurial-revolution

Kantis, H., & Federico, J. (2020). A dynamic model of entrepreneurial ecosystems evolution. Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business, 5(1), 182-220. https://doi.org/10.1344/jesb2020.1.j072

Lastra, J. F. R., Macías, M., & Pradilla, C. A. (2022). Importancia del ecosistema emprendedor regional: un análisis de su función y articulación. Desarrollo Gerencial, 14(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.17081/dege.14.1.4945

Linne, J. (2014). Dos generaciones de nativos digitales. Intercom, 37(2), 203-221. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-584420149

Luu, T. T., & Venkatesh, S. (2010). Organizational culture and technological innovation adoption in private hospitals. International Business Research, 3(3), 144. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v3n3p144

McLean, L. D. (2005). Organizational Culture's Influence on Creativity and Innovation: A Review of the Literature and Implications for Human Resource Development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(2), 226–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422305274528

Moreno-Domínguez, M.J., Martín-Zamora, M.P., Serrano-Czaia, I. & Rodríguez-Ariza, L. (2022). Reputation and leadership: a study about reputational transfer in family and non-family firms. Cuadernos de Gestión, 22(1), 65-80. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.211465mm

Naranjo-Valencia, J. C., & Hernández, G. C. (2018). Model of culture for innovation. En IntechOpen eBooks. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.81002

Oh, D., Phillips, F. M., Park, S., & Lee, E. (2016). Innovation Ecosystems: A Critical Examination. Technovation, 54, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2016.02.004

Oksanen, K., & Ståhle, P. (2013). Physical environment as a source for innovation: investigating the attributes of innovative space. Journal Of Knowledge Management, 17(6), 815-827. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-04-2013-0136

Ospina, M. C., Vergara, J. A. V., & Rozo, L. M. (2021). Innovación sostenible, cultura organizacional y gestión humana: una revisión sistemática de literatura. Publicaciones e Investigación, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.22490/25394088.5610

Ouchi, W. G., & Wilkins, A. L. (1985). Organizational Culture. Annual Review of Sociology, 11, 457–483. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2083303

Palacios-Maldonado, M. (2000). APRENDIZAJE ORGANIZACIONAL. Conceptos, procesos y estrategias. Hitos de Ciencias Económico Administrativas, 25, 25-31. https://bit.ly/3WuwSEQ

Pascale, R. T., & Athos, A. G. (1981). The art of Japanese management. Business Horizons, 24(6), 83-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(81)90032-x

Paul, J., & Rosado-Serrano, A. (2019). Gradual Internationalization vs Born-Global/International new venture models. International Marketing Review, 36(6), 830-858. https://doi.org/10.1108/imr-10-2018-0280

Pedraja-Rejas, L., Rodríguez-Ponce, E., & Muñoz-Fritis, C. (2021). Liderazgo transformacional y cultura innovativa: efectos en la calidad institucional. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 26(96), 1004-1018. https://doi.org/10.52080/rvgluz.26.96.2

Pereira, R., MacLennan, M. L. F., & Tiago, E. F. (2020). Interorganizational cooperation and eco-innovation: a literature review. International Journal of Innovation Science, 12(5), 477-493. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijis-01-2020-0008

Pértegas, S., & Fernández, P. (2002). Investigación cuantitativa y cualitativa. Cadernos de Atención Primaria, 9(2), 76-78. http://metabase.uaem.mx/handle/123456789/1451

Rueda-Barrios, G., Gonzalez-Bueno, J., Rodenes, M., & Moncaleano, G. (2018). La cultura organizacional y su influencia en los resultados de innovación en las pequeñas y medianas empresas. Revista ESPACIOS, 39(42). http://es.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n42/18394236.html

Santiago-Torner, C. (2023). Ethical Climate and Creativity: The Moderating Role of Work Autonomy and the Mediator Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Cuadernos de Gestión, 23(2), 93-105. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.221729cs

Schein, E. H. (1978). Career dynamics: Matching individual and organizational needs. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA01260066

Schein, E. H. (1993). Organizational culture and leadership. Long Range Planning, 26(5), 153. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(93)90120-5

Stanley, T., Davidson, P., & Matthews, J. (2014). Creative work environments and employee engagement: exploring potential links and possibilities. Zeszyty Naukowe. https://doi.org/10.15678/znuek.2014.0933.0903

Tippmann, E., Ambos, T. C., Del Giudice, M., Monaghan, S., & Ringov, D. (2023). Scale-ups and scaling in an international business context. Journal of World Business, 58(1), 101397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101397

Trillo-Holgado, M. A., León-Urbán, C., & López-Caballero, R. (2022). La importancia de las capacidades dinámicas en el replanteamiento de una ventaja competitiva innovadora. Estudio de caso en empresas tecnológicas cordobesas. Revista de Estudios Andaluces, 43, 125-143. https://doi.org/10.12795/rea.2022.i43.07

Van Looy, A. (2021). A quantitative and qualitative study of the link between business process management and digital innovation. Information & Management, 58(2), 103413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103413